In 2022 alone, over 20 million people were diagnosed with cancer, and nearly 10 million died from the disease, according to the World Health Organization. While the reaches of cancer are massive, the answer to more effective treatments may be hidden within a microscopic cell.

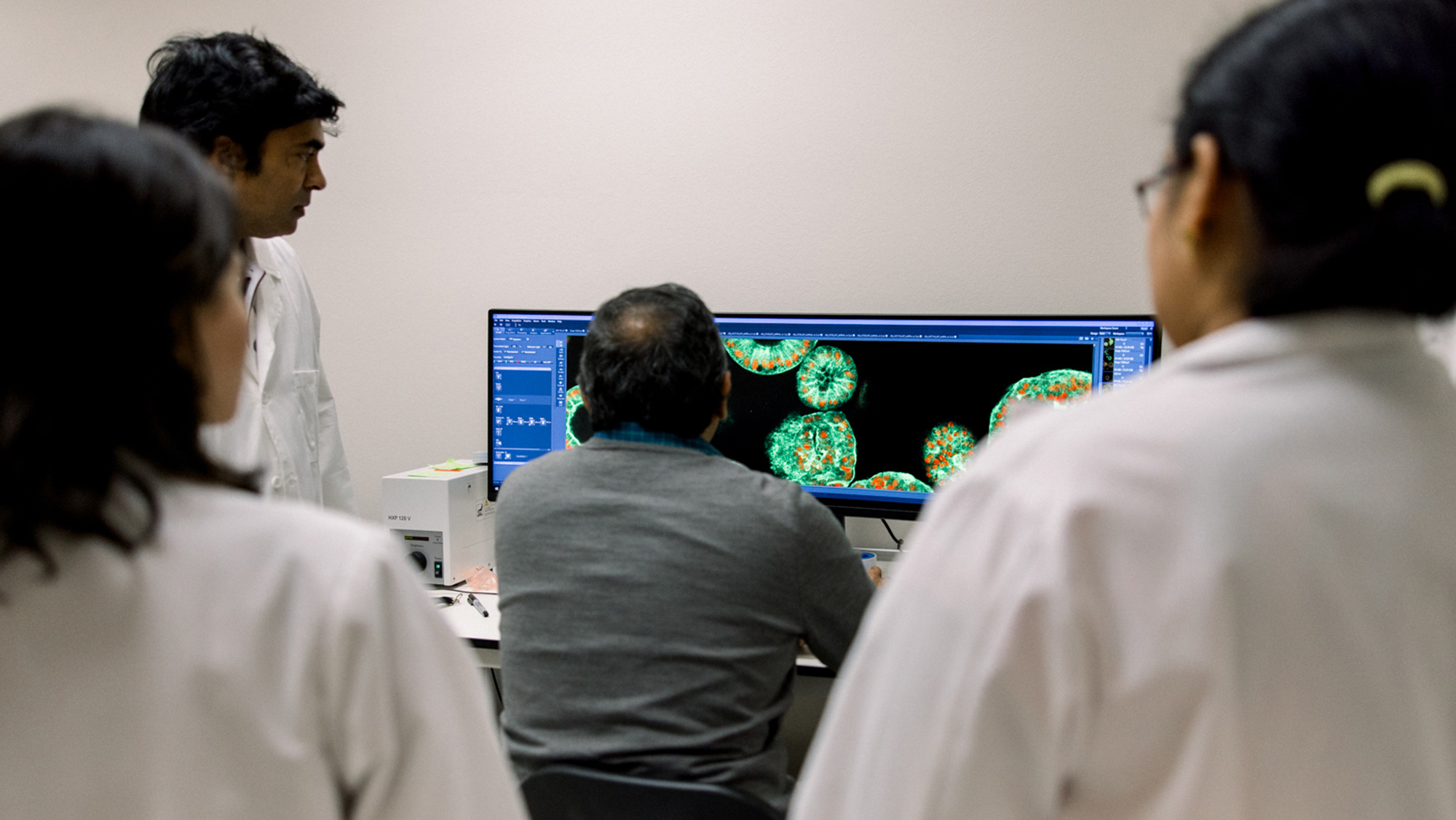

Texas A&M University graduate students Samere Zade of the biomedical engineering department and Ting-Ching Wang of the chemical engineering department led a study by the Lele Lab that uncovered new details about the mechanism behind cancer progression.

Published in Nature Communications, the article explores the influence the mechanical stiffening of the tumor cell’s environment may have on the structure and function of the nucleus.

“Cancer has proven to be a difficult disease to treat. It is extremely complex and the molecular mechanisms that enable tumor progression are not understood,” said Dr. Tanmay Lele, joint faculty in the biomedical engineering and chemical engineering departments. “Our findings shed new light into how the stiffening of tumor tissue can promote tumor cell proliferation.”

In the article, researchers reveal that when a cell is faced with a stiff environment, the nuclear lamina — scaffolding that helps the nucleus keep its shape and structure — becomes unwrinkled and taut as the cell spreads on the stiff surface. This spreading causes yes-associated protein (YAP), the protein that regulates the multiplication of cells, to move to the nucleus.

That localization can cause increased cell proliferation, which may explain the rapid growth of cancer cells in stiff environments.

Drugs or treatments could be designed to soften the tumor environment, disrupting the physical cues that help cancer cells thrive.

“The ability of stiff matrices to influence nuclear tension and regulate YAP localization could help explain how tumors become more aggressive and perhaps even resistant to treatment in stiffened tissues,” Zade said.

These findings build on Lele’s previous discovery that the cell nucleus behaves like a liquid droplet. In that work, researchers found that a protein in the nuclear lamina called lamin A/C helps maintain the nucleus’ surface tension. In the most recent study, it was found that reducing the levels of lamin A/C decreases the localization of YAP, in turn decreasing rapid cell proliferation.

“The protein lamin A/C plays a key role here — reducing it made cells less responsive to environmental stiffness, particularly affecting the localization of a key regulatory protein (YAP) to the nucleus,” Zade explained.

Although seemingly complex and specialized, Zade and Lele believe the broader implications of their discovery may guide future treatments for cancer.

“Uncovering how matrix stiffness drives nuclear changes and regulates key pathways, like YAP signaling, opens the door to developing therapies that target these mechanical pathways,” Zade explained. “Drugs or treatments could be designed to soften the tumor environment, disrupting the physical cues that help cancer cells thrive. Lamin A/C and related nuclear mechanics could become targets for cancer treatments.”

Moving forward, the Lele Lab aims to investigate the extent to which their discoveries apply to tumors derived from patients.

For this work, the Lele Lab was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas, and the National Science Foundation. Funding for this research is administered by the Texas A&M Engineering Experiment Station, the official research agency for Texas A&M Engineering.