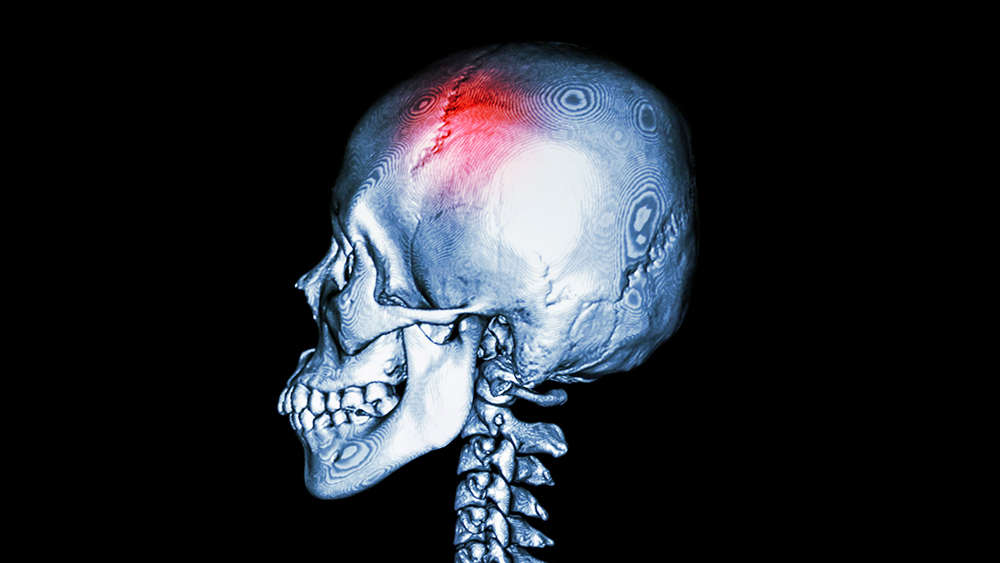

Subtle variations in the architecture of the 22 bones of the skull give each one of us a unique facial profile. Hence, repairing the shape of skull defects, in the event of a fracture or a congenital deformity, calls for a technique that can be tailored to an individual’s face or head structure.

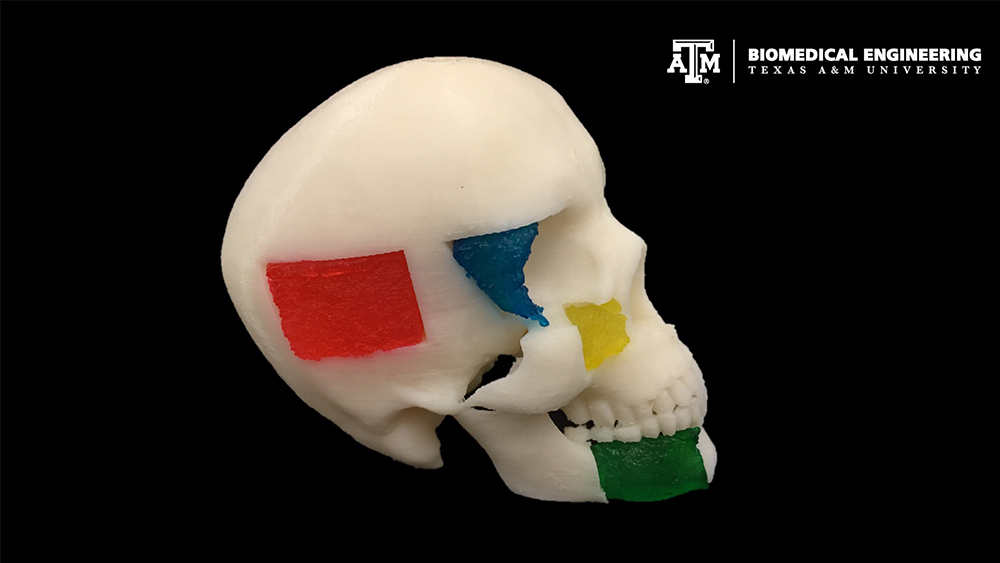

In a new study, researchers at Texas A&M University have combined 3D printing, biomaterial engineering and stem cell biology to create superior, personalized bone grafts. When implanted at the site of repair, the researchers said these grafts will not only facilitate bone cells to regrow vigorously but also serve as a sturdy platform for bone regeneration in a desired, custom shape.

“Materials used for craniofacial bone implants are either biologically inactive and extremely hard, like titanium, or biologically active and too soft, like biopolymers,” said Dr. Roland Kaunas, associate professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering. “In our study, we have developed a synthetic polymer that is both bioactive and mechanically strong. These materials are also 3D printable, allowing custom-shaped craniofacial implants to be made that are both aesthetically pleasing and functional.”

A detailed report on the findings was published online in the journal Advanced Healthcare Materials in March.

Each year, about 200,000 injuries occur to bones of the jaw, face and head. For repair, physicians often hold these broken bones in place using titanium plates and screws so that surrounding bone cells can grow and form a cover around the metal implant. Despite its overall success in aiding bone repair, one of the major drawbacks of titanium is that it does not always integrate into bone tissue, which can then cause the implant to fail, requiring another surgery in advanced cases.

Thus, biocompatible polymers, particularly a type called hydrogels, offer a preferable alternative to metal implants. These squishy materials can be loaded with bone stem cells and then 3D printed to any desired shape. Also, unlike titanium plates, the body can degrade hydrogels over time. However, hydrogels also have a known weakness.

“Although the pliability of hydrogel-based materials makes them good inks for 3D bioprinting, their softness compromises the mechanical integrity of the implant and the accuracy of printed parts,” said Dr. Akhilesh Gaharwar, associate professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering.

To increase the stiffness of the hydrogel, the researchers developed a nanoengineered ionic-covalent entanglement or “NICE” recipe containing just three main ingredients: an extract from seaweed called kappa carrageenan, gelatin, and nanosilicate particles that both stimulate bone growth and mechanically reinforce the NICE hydrogel.

First, they uniformly mixed the gelatin and kappa carrageenan at microscopic scales and then added the nanosilicates. Gaharwar said the chemical bonds between these three items created a much stiffer hydrogel for 3D bioprinting — with an almost eight-fold increase in strength compared to individual components of NICE bioink.

Next, they added adult stem cells to 3D parts printed with NICE ink and then chemically induced the stem cells to convert into bone cells. Within a couple of weeks, the researchers found that the cells had grown in numbers, producing high levels of bone-associated proteins, minerals and other molecules. In aggregate, these cell secretions formed a scaffold, known as an extracellular matrix, with a unique composition of biological materials needed for the growth and survival of developing bone cells.

When the scaffolds are fully developed, the researchers noted that the bone cells could be removed from the scaffold and the hydrogel-based implant can then be inserted into the site of skull injury where the surrounding, healthy bones initiate healing. Over time, the 3D printed scaffolds biodegrade, leaving behind a healed bone in the right shape.

“The idea is to have the body’s own bone repair machinery participate in the repair process,” said Kaunas. “Our biomaterial is enriched with this regenerative extracellular matrix, providing a fertile environment to naturally trigger bone and tissue restoration.”

The researchers explained that the 3D-printed scaffolds provide a strong structural framework that facilitates the attachment and growth of healthy bone cells. Also, they found that developing bone cells penetrate through the synthetic material, thereby increasing the functionality of the implant.

“Although our current work is focused on repairing skull bones, in the near future, we would like to expand this technology for not just craniomaxillofacial defects but also bone regeneration in cases of spinal fusions and other injuries,” said Kaunas.

Other contributors to this study include Dr. Candice Sears, Eli Mondragon, Zachary Richards, Dr. Nick Sears and Dr. David Chimene from the Texas A&M Department of Biomedical Engineering; and Eoin McNeill and Dr. Carl A. Gregory from the Texas A&M Health Science Center.

This research is funded by the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation.