Contrary to what was once popular belief, microwaves don’t cause cancer. It’s a decades-old concern that may evoke a vague memory of nostalgia: a young child standing in front of a microwave, peering through the dimly-lit door, only to be told to take a few steps back or they could catch an inexplicable illness or worse — radiation poisoning.

Thanks to advancements in science, engineering and technology, we now know that microwaves are safe, effective and efficient. However, recent research from Texas A&M University reveals that exposure to certain extremely high-powered microwave and radio frequencies may result in high stresses within the brain.

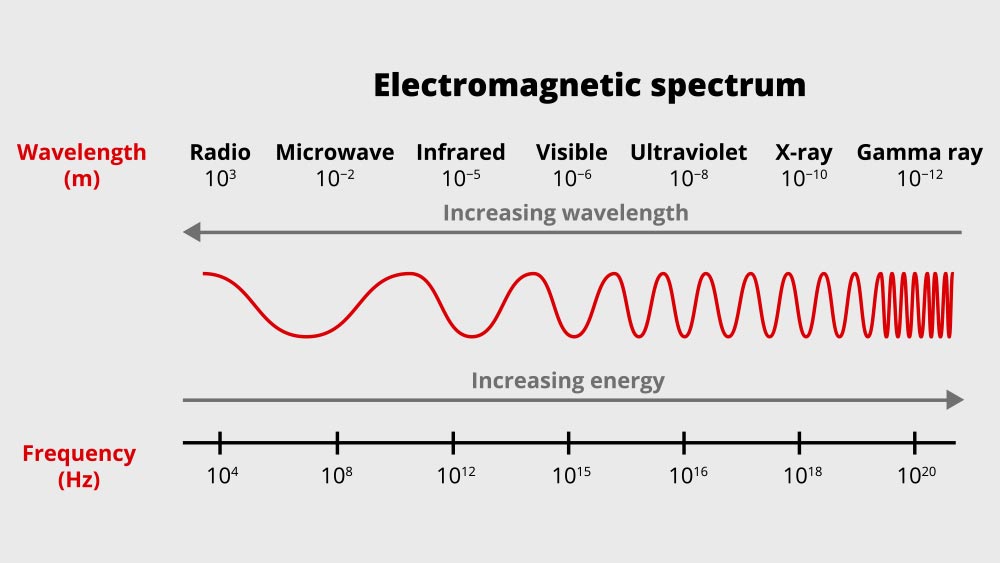

Dr. Justin Wilkerson, assistant professor in the J. Mike Walker ’66 Department of Mechanical Engineering, in collaboration with researchers at the U.S. Army Research Laboratory and the Air Force Research Laboratory, began investigating the effects of high-powered pulsed microwaves on the human body. Most commonly used for rapid cooking, microwaves are a type of electromagnetic radiation that fall between radio and infrared light on the electromagnetic spectrum.

Using computational modeling, the team’s two-simulation approach first calculates the specific absorption rate (SAR) of planar electromagnetic waves on a 3D model of a human body. The SAR values are then used to calculate changes in temperature throughout the head and brain. Those temperature changes are then used to determine how the brain tissue physically alters in response to the high-intensity microwaves.

“The microwave heating causes spatially varying, rapid thermal expansion, which then induces mechanical waves that propagate through the brain, like ripples in a pond,” said Wilkerson. “We found that if those waves interact in just the right way at the center of the brain, the conditions are ideal to induce a traumatic brain injury.”

Published in Science Advances, Wilkerson’s research revealed that when applying a small temperature increase over a very short amount of time (microseconds), potentially injurious stress waves are created. Imagine all of the microwave energy needed to pop a bag of popcorn condensed into one-millionth of a second and then directed at the brain.

However, there’s no need to worry about every day exposure to microwaves or radiofrequency levels. Wilkerson’s study included magnitudes of power far greater than anything the average human will be exposed to.

“Although the required power densities at work here are orders of magnitude larger than most real-world exposure conditions, they can be achieved with devices meant to emit high-power electromagnetic pulses in military and research applications,” said Wilkerson.

Wilkerson and the team used finite element simulations as part of their computational modeling — the same models that have been used to predict traumatic brain injury in car crashes, football impacts and even explosive blasts on the battlefield. By applying it to a new energy deposition, the microwave, Wilkerson has opened the door for more research to be conducted on the interactions between the biological body and electromagnetic fields and its applications.