Throughout her life, Dr. Christie Bergerson ’11 ’15 knew she wanted to be a physician, until she didn’t. The summer after her freshman year, she shadowed a surgeon.

“I hated it,” she said. “It was the same thing over and over and over again. I found it much more interesting to think about the tools that were being used and how they figured out how to use a laser scalpel that only cuts right where it needs to cut or how we got the imaging modalities to work to where they're safe but still effective.”

Bergerson entered Texas A&M University as a biomedical engineering major after some advice from her grandfather, Dr. Rodger Koppa, associate professor emeritus in the Wm Michael Barnes ’64 Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering. That decision allowed her to easily shift her focus from medical school to industry.

After her bachelor’s degree, she remained at Texas A&M for her Ph.D., although her doctoral research was nontraditional. Instead of one project, she completed a survey Ph.D. that involved several projects that added up to the knowledge requirement for graduation. Some of these projects involved her work on the development of a bone implant interface for total knee replacement and a bone cuff for fractures.

“I found that my experience with this survey Ph.D. better reflected the needs and utilities that I now see in industry,” Bergerson said. “I tend to gravitate toward opportunities that are diverse in subject matter.”

After graduation, she joined Abbott Laboratories as a verification and validation engineer to work in next generation in vitro diagnostics technology outside of the body. Bergerson’s role involved drafting test protocols to ensure the instrument and its components would function as intended, and she also helped troubleshoot problems when the results of testing were different than expected. Once the technology was approved by various regulatory agencies and launched in the U.S. and internationally, Bergerson was promoted to systems engineer.

“The position is a single point of responsibility that sits in design review meetings and assures continuity across the system,” Bergerson said. “When I'm talking about a medical device system, particularly for these clinical lab in vitro diagnostics analyzers, we're talking a system with over 300 parts. It's very complex.”

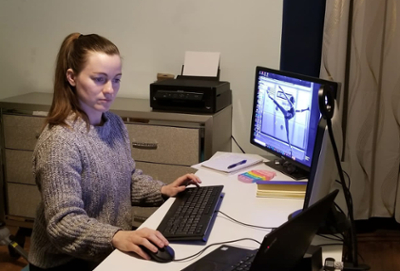

In 2019, Bergerson was recruited by Exponent to serve in a similar role, but her new consultant position involves working on projects for multiple companies. Her areas of expertise are in vitro diagnostics, orthopedic biomechanics and artificial intelligence/software in medical devices.

Bergerson has not forgotten the people who impacted her as a student, and she works to help guide future engineers. She serves as an adjunct professor in biomedical engineering at Johns Hopkins University and has lectured at Texas A&M, Drexel University and the University of Maryland. She enjoys acting as a mentor to students.

“I hope they get perspective from someone who's currently going through it, because the policies, especially for artificial intelligence, are being updated continuously,” she said. “I also hope they get some validation as to what aspects of their education are important versus which ones you don't use quite as often in industry.”

Bergerson’s advice to students is to stress less on subject matter. Many of the questions she receives relate to students exploring career paths with a narrow focus, looking at which particular topic they want to commit to. Instead, she encourages people to consider what parts of projects, jobs or other experiences they’ve enjoyed — such as working in a team, working in a lab, working at home, etc. — to better identify what kind of job they’d like.

“If you can identify those fundamental elements that define your ideal job, the background information you need for a specific job will come easily,” Bergerson said. “When I switched from orthopedic biomechanics to in vitro diagnostics for my first job, I thought it was going to be terrible. I picked up the topic within a couple of months. The hard part was making sure that I liked the research environment. You'd be surprised; the flavor of engineering is so much less important than if you're happy day to day.”