Our bodies consist of an intricate network of blood vessels that form the vascular, or circulatory system. The role of this system is to transport blood to the organs for their nourishment. Like other bodily systems, the vascular system suffers from diseases ranging from bleeding disorders to blood clots or thrombosis. In fact, vascular diseases are ranked among the leading cause of death worldwide as they are relatively misunderstood and the therapeutic approaches that exist or are in development are inadequate.

A research team at Texas A&M University is working to create new tools that can help in the treatment of these diseases by leveraging a new bioengineering technology, called “organ-on-a-chip.” The shortfalls in treatment are attributed primarily to the fact that discovery and therapeutic programs rely heavily on results from animal models that poorly predict how the human body will respond to drug treatments.

“This study advances organ-on-chip technology in the direction of precision and personalized medicine,” said Dr. Abhishek Jain, assistant professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering and co-author on the study.

Organ-on-a-chip models provide an innovative approach to bypass animal studies and directly test drugs in a humanized microphysiological environment. But these models are also limited in their precision because they rely on cell sources that are not always representative of the disease or condition being modeled.

While it would be sometimes ideal for researchers to be able to use primary cells from biopsies, which are directly cultured from their source organ tissue or blood cells as they would provide a highly reliable source of cells for organ-on-chip technology, biopsies are still not always a viable option as patient tissue samples are naturally limited and often require sophisticated surgeries.

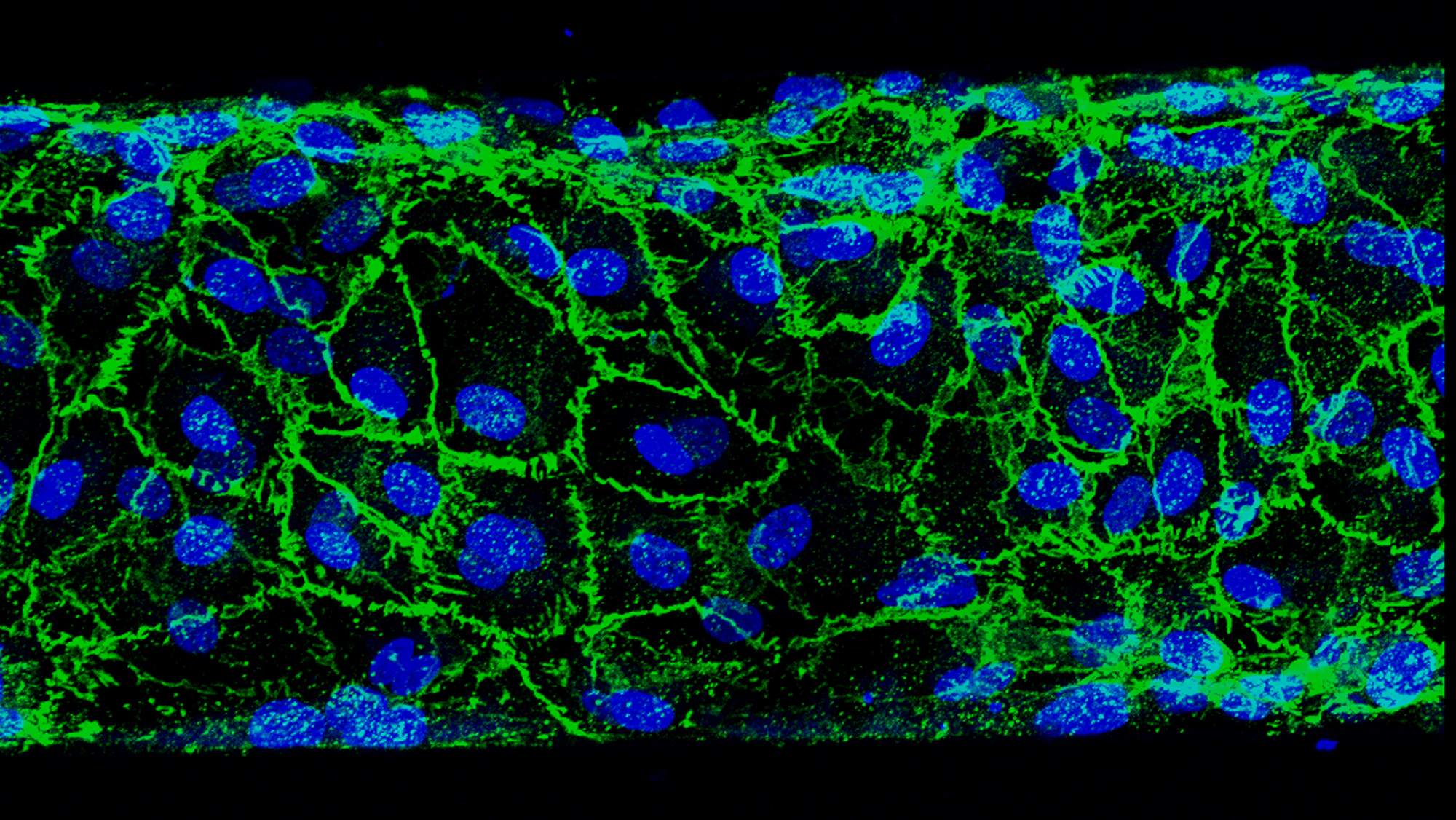

However, Jain and his team have now proposed a different route in the study they recently published in the scientific journal Lab on a Chip. They looked into the endothelial cells that are present in blood samples that play roles in regenerating the interior surface lining of blood vessels, a relatively understudied cell subpopulation. Specifically, they mined the blood outgrowth endothelial cells (BOECs) and applied them in organ-on-chips.Taking BOECs from healthy or diabetic patients, the team formed vascular organ-chips or “vessel-chips.”

They then studied how well the BOECs demonstrated inflamed vascular tissue and found that within the organ-chips, the diabetic BOECs functioned the same way as a blood vessel of a diabetic patient. Therefore, their device is a reliable model for understanding vascular diseases and predicting therapeutic outcomes at a disease and patient-specific level.

By more accurately mimicking a patient’s vascular condition, the study suggests that BOECs may advance the organ-chip technology and could potentially be easily deployed in preclinical research or personalized medical applications to more efficiently treat diseases.

“New drugs and toxins can be tested on these vessel-chips much more effectively, and the results obtained from these studies in preclinical trials will be expected to correlate much more closely to human clinical trials,” Jain said.