A passenger airliner full of people lines up on the runway preparing for takeoff. As the engines rev up, the sound is a dull roar to the passengers inside the craft. However, this sound is an indication of a process that could impact the safety and reliability of the plane, a system that researchers at Texas A&M University are seeking to improve.

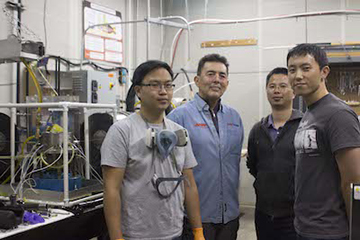

Dr. Luis San Andrés, Mast-Childs Chair in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Texas A&M, works on multiple projects in the Turbomachinery Laboratory. His work in rotordynamics includes novel squeeze film dampers, which help reduce vibrations within a jet engine, creating more reliable equipment that is safer and more comfortable to the ears of passengers. The long-term project has been funded by Pratt & Whitney Engines since 2008.

"You turn on an airplane engine and don't turn it off for three years; it's not like your car, which you turn on and off every day," San Andrés said. "You can't do that with aircraft because it takes a lot of warm up to come up to speed. The moment you turn them off, they cool off and parts contract and don't work as well.

Inside the jet engine there is a space smaller than a human hair between the frame of the engine and the turbines. The space is filled with lubricant that prevents the equipment from wearing down. During the warmup period, the lubricated squeeze film dampers are vital to help decrease vibration from the rotating gas turbine engine that makes the overall plane safer by reducing wear on the airplane. The goal of San Andrés' research is to reduce the time it takes to warm up the engine, as well as to continue to increase the safety and efficiency of aircraft jet engines.

San Andrés said the concept is similar to the fluids inside the human body. Between the knee bones for example, there is a packet of synovial fluid that cushions impact.

"When you jump or run there is impact, the fluid prevents the bones from hitting each other and wearing down. These dampers only work under compression, they cannot work under tension," San Andrés said. "Inside the jet engine there is squeeze lubricant around the surface of the rotor that helps to keep it going and operating smoothly."

Since aircrafts carry little lubricant to reduce weight and volume, squeeze film dampers during operation are prone to draw air in the film. This dynamic process causes the oil and air to mix and the air bubbles reduce the damping ability. San Andrés' students are testing dampers with controlled bubbly oil mixtures to quantify damper degradation in realistic testing conditions.

Along with the physical research, San Andrés' lab has developed computational programs that are used by the industry today. But whether it's the physical research or computational research, one of the goals of San Andrés is to teach engineering staff and students the importance of predictive maintenance, a common theme across his varied projects in the turbomachinery lab.

"In engineering the last thing that you want is to solve a problem, you solve problems before they occur during the design stage," San Andrés said. "You have to figure out there will be a crazy professor who's going to test how to break it and it has to survive.

"The best engineers aren't the ones who solve problems, they're the ones who anticipate the problems and needs in a product," San Andrés said. "The best engineers create a need and change the world."

San Andrés said his work falls in line with the mission statement of the turbomachinery lab, which is to educate students, perform research that is state-of-the-art as a tier one university should have and provide continuing education. His work has a direct impact on industry, as 95 percent of his projects are industry funded. San Andrés also works to promote engineering education, giving students the skills necessary to survive in a modern fast-paced world. His projects typically support a dozen graduate students and professional research staff each year.