Imagine designing and building a machine to perform a task it cannot see its way through, only feel. You must program it to solve problems and adjust its own speed and progress to avoid hazardous situations and failure. Once your machine is started, you have to trust it to function all on its own.

Three graduate students, Tyrell Cunningham, Ibrahim El-Sayed and Enrique Zarate Losoya, from the Harold Vance Department of Petroleum Engineering at Texas A&M University won the 2017 Drillbotics Competition this summer by doing just that. They designed and built a miniature automated drilling rig that uses sensors and computer logistics to drill a vertical well in a test formation of unknown composition without any human intervention.

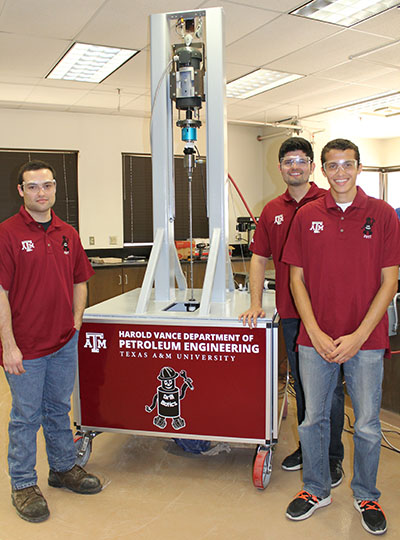

Aggie Drillbotics team (left to right): Tyrell Cunningham, Enrique Zarate Losoya and Ibrahim El-Sayed

What is Drillbotics?

The annual Drillbotics competition originated when several Society of Petroleum Engineering members established the Drilling Systems Automation Technical Section (DSATS) to accelerate the use of automation in the drilling industry. The goal of DSATS is to link surface machines to downhole machines, tools and measuring systems to create an automated system that improves drilling safety and efficiency. The group thought student competitions were the perfect way to introduce the topic.

DSATS reached out to several universities to see if their students could create and manage the multi-disciplinary teams needed to succeed. Confident the idea would work, DSATS held the first Drillbotics competition in 2015, and Aggies have been present from the start.

The Aggie team

Teams from Texas A&M placed second in the first two years of competition. This year, when more teams entered and Drillbotics upped the difficulty level, the Aggies pulled out all the stops and took first place.

The team’s rig is so impressive it has been used by two National Science Foundation-funded undergraduate students this summer to conduct research into drilling parameters and vibrations on wellbore patterns and their effect on drilling dysfunctions.

“Tyrell, Ibrahim, and Enrique put in a lot of work and it showed,” said team advisor Dr. Sam Noynaert, assistant professor in the department. “They were up against the largest group of schools the competition has seen. The things they were able to accomplish in terms of sensors, machining and design were very impressive. The presentation they made to the judges was extremely well done and was likely a key reason for their win.”

Most teams are made up of students from several engineering disciplines. This was the first year all the Aggie members were petroleum engineering majors, but because they were familiar with mechanical, computer and petroleum engineering disciplines, they succeeded.

Automated drilling rigs

Crafting an automated two-meter tall drilling rig is no small feat. Students are given two semesters, fall and spring, to accomplish the task. During the fall semester students must research automated drilling and draw up their designs. During the spring semester the teams construct their machine and deal with purposely introduced challenges similar to what industry engineers encounter in the field.

“The design phase’s main challenge is actually afterward, in the transfer from design to implementation,” said Noynaert. “They ran into issues with the control algorithms, data handling, sensors and sensor communication, and the need for significant custom machining and manufacturing.”

Because of cost and time constraints, as well as the highly specialized nature of what they needed, the team machined a variety of custom top-drive parts themselves. Department staff member John Maldonado spent time with the student on this, providing advice and patience.

“These parts were necessary to allow a wired downhole sensor to send high rates of vibration data to the surface while drilling, all while the drillstring was rotating at over 1,500 rpm (revolutions per minute),” said Noynaert. “They were able to solve each problem on time and under budget.”

Teams were purposely limited on equipment in some areas, especially the drillpipe.

“The pipe is intentionally thin-walled and weak, making it difficult to transfer weight and rpm to the bit without breaking the pipe,” said Noynaert. “This makes the control system’s recognition and response to drilling dysfunctions critical since an incorrect response could cause a catastrophic equipment failure.”

The competition

Judges from DSATS visit each university after the spring semester ends, grading team presentations and observing each rig’s performance. They provide each team with a “formation” for the rig to drill, a block sealed with concrete containing unknown compositions that include one or more drilling hazards.

“This year’s sample had varying strengths of formations, from sandstone to asphalt to even a layer of rubber, all intended to cause drilling dysfunctions that would either result in an equipment failure or slow down the drilling significantly,” said Noynaert. “This year they had to overcome severe whirl (downhole bit and drillstring vibrations) and some stick-slip (variations in torque and rpm).”

The team can only use two buttons during the competition: start and stop. The rig must do everything else on its own.

“This is an automated rig, meaning there is no fixing a problem by hand or allowing a person to make a real-time decision for the rig,” said Noynaert. “It must do it all on its own, meaning any failure in any system results in an overall failure in the final test.”

Rigs are graded on drill speed and borehole straightness and quality. Teams are scored on their ability to present and explain their work, including safety measures, budget and design choices. Judges are looking for creativity, innovation and reliability.

The results

Ten universities submitted designs for the 2017 competition and seven progressed to the finals. Texas A&M took first place, with the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in second, and the University of Stavanger and the University of Oklahoma tied for third.

“Through two semesters you have learned things that are not in the textbooks,” wrote Fred Florence, chair of the Drillbotics committee for DSATS, to the participants. “You experienced the thrill of invention followed by the intense effort necessary to develop your innovation into a working prototype. All of you experienced times when things did not go as planned, yet you found ways to keep moving forward. Congratulations to all of you.”

Though the team was funded by the department and was provided three faculty advisors and one staff member for guidance, Noynaert was quick to point out that Cunningham, El-Sayed and Zarate Losoya did the majority of the work without assistance. They spent countless hours and late nights on the challenge, earning only three hours of class credit.

“What they accomplished is not just amazing relative to what one would expect from a student, but is actually comparable or even better than what a group of practicing engineers in industry would produce,” said Noynaert. “What they and the other schools’ teams are doing will have an impact on the industry.”