From aerospace and defense to digital dentistry and medical devices, 3-D printed parts are used in a variety of industries. Currently, 3-D printed parts are very fragile and traditionally used in the prototyping phase of materials or as a toy for display. A doctoral student in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at Texas A&M University has pioneered a countermeasure to transform the landscape of 3-D printing today.

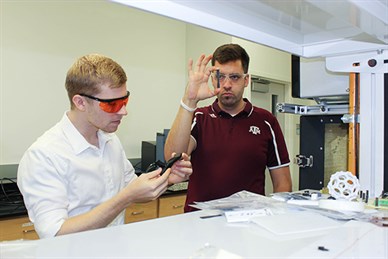

Brandon Sweeney and his advisor Dr. Micah Green, associate professor in the Department of Chemical Engineering, discovered a way to make 3-D printed parts stronger and immediately useful in real-world applications. Sweeney and Green applied the traditional welding concepts to bond the submillimeter layers in a 3-D printed part together, while in a microwave.

Sweeney began working with 3-D printed materials while employed at the Army Research Laboratory at the Aberdeen Proving Grounds in Maryland.

“I was able to see the amazing potential of the technology, such as the way it sped up our manufacturing times and enabled our CAD designs to come to life in a matter of hours,” Sweeney said. “Unfortunately, we always knew those parts were not really strong enough to survive in a real-world application.”

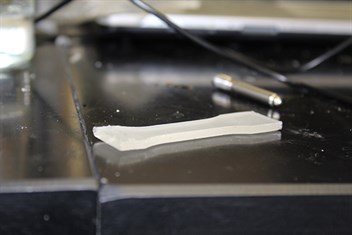

3-D printed objects are comprised of many thin layers of materials, plastics in this case, deposited on top of each other to form a desired shape. These layers are prone to fracturing, causing issues with the durability and reliability of the part when used in a real-world application, for example a custom printed medical device.

3-D printed objects are comprised of many thin layers of materials, plastics in this case, deposited on top of each other to form a desired shape. These layers are prone to fracturing, causing issues with the durability and reliability of the part when used in a real-world application, for example a custom printed medical device.

“I knew that nearly the entire industry was facing this problem,” Sweeney said. “Currently, prototype parts can be 3-D printed to see if something will fit in a certain design, but they cannot actually be used for a purpose beyond that.”

When Sweeney started his doctorate, he was working with Green in the Department of Chemical Engineering at Texas Tech University. Green had been collaborating with Dr. Mohammad Saed, assistant professor in the electrical and computer engineering department at Texas Tech, on a project to detect carbon nanotubes using microwaves. The trio crafted an idea to use carbon nanotubes in 3-D printed parts, coupled with microwave energy to weld the layers of parts together.

“The basic idea is that a 3-D part cannot simply be stuck into an oven to weld it together because it is plastic and will melt,” Sweeney said. “We realized that we needed to borrow from the concepts that are traditionally used for welding parts together where you’d use a point source of heat, like a torch or a TIG welder to join the interface of the parts together. You’re not melting the entire part, just putting the heat where you need it.”

Since the layers making up the 3-D printed parts are so tiny, special materials are utilized to control where the heat hits and bonds the layers together.

“What we do is take 3-D printer filament and put a thin layer of our material, a carbon nanotube composite, on the outside,” Sweeney said. “When you print the parts out, that thin layer gets embedded at the interfaces of all the plastic strands. Then we stick it in a microwave, we use a bit more of a sophisticated microwave oven in this research, and monitor the temperature with an infrared camera.”

“What we do is take 3-D printer filament and put a thin layer of our material, a carbon nanotube composite, on the outside,” Sweeney said. “When you print the parts out, that thin layer gets embedded at the interfaces of all the plastic strands. Then we stick it in a microwave, we use a bit more of a sophisticated microwave oven in this research, and monitor the temperature with an infrared camera.”

The technology is patent-pending and licensed with a local company, Essentium Materials. The materials are produced in-house, where they also design the printer technology to incorporate the electromagnetic welding process into the 3-D printer itself. While the part is being printed, they are welding it at the same time. They are currently in beta mode, but this has the potential to be on every industrial and consumer 3-D printer where strong parts are needed.

“If you're an engineer and if you actually care about the mechanical properties of what you're making, then this ideally would be on every printer in that category,” Sweeney said.

The team recently published a paper “Welding of 3-D Printed Carbon Nanotube-Polymer Composites by Locally Induced Microwave Heating,” in Science Advances.