Mikayla Barry always knew she wanted to make a difference in people’s lives, but the undergraduate biomedical engineering major had no idea she would be helping develop a potentially life-saving technology so soon after embarking upon her academic career at Texas A&M University.

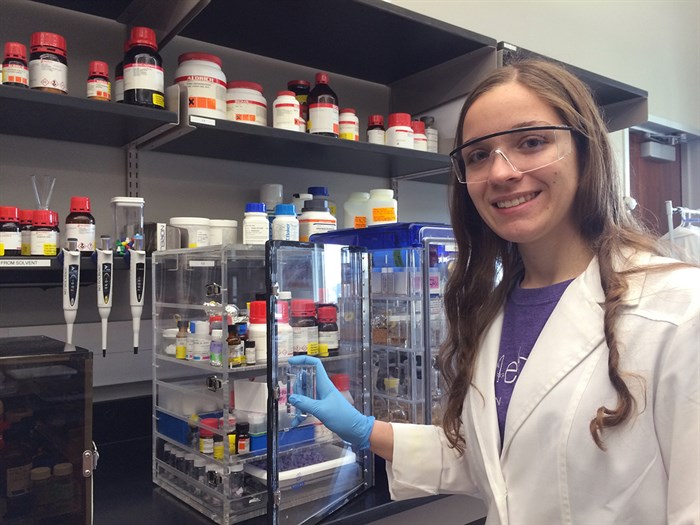

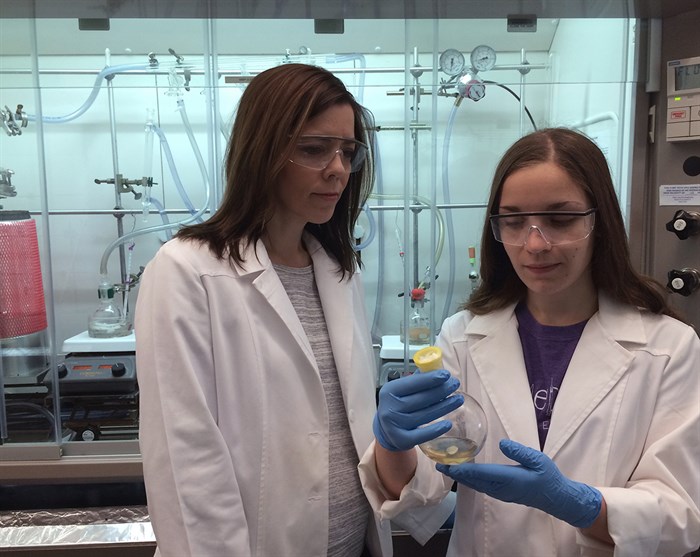

Merely a year into the pursuit of her degree, the 20-year-old Barry is working to develop a coating for medical devices that prevents clotting as well as infection. She’s part of a research team led by Associate Professor Melissa Grunlan, an authority on biomaterials and regenerative therapies from the university’s Department of Biomedical Engineering.

Though it’s still in its initial stages of development, early tests indicate the coating – which can be applied to a variety of implantable medical devices such as catheters – demonstrates a reduction in protein adhesion as well as common bacteria adhesion, Grunlan notes. In other words, blood and bacteria are less able to stick to the coating, meaning fewer clots and a decreased chance of infection. That’s particularly important for patients treated with catheters, Grunlan explains.

“People who have end-stage renal disease may receive dialysis with a catheter, but these catheters are very prone to failure due to thrombosis, or clotting, on the device, Grunlan says. “The worst-case scenario is that the clot can be dislodged and lead to a potentially fatal embolism.”

"It’s a learning experience that integrates what I am learning in the classroom with what I would like to do in a laboratory environment someday after I graduate.”

Looking to overcome this serious issue, medical professionals have relied on the anti-clotting drug heparin, which is typically locked within the catheter, but that approach can result in the inadvertent leaking of heparin into a patient. When this happens, Grunlan notes, the patient is essentially on a blood thinner during a time when he or she may require surgery due to poor health. It’s a bad combination, and what’s more, the outer surfaces of the catheter remain susceptible to clotting, she explains.

A better solution, Grunlan believes, lies in the manufacturing of a better catheter – one that’s more effective at preventing clotting and infection and less of a risk to patients. Achieving this, however, is no easy task; it requires manipulating the materials from which the catheter is made on a molecular level… That’s where Barry comes in.

While such work may seem exceedingly complex for the average sophomore, the biomaterials research being conducted by Barry is right in her wheelhouse. An academic standout with a lifelong love for chemistry (her mother is a chemistry teacher) and the medical field, the Bryan, Texas native was eager to work in a lab environment.

“Coming to Texas A&M I was amazed by the biomedical engineering department and the applications that were available in pretty much anything medically related,” she said. “When I realized that I could combine that with chemistry, I knew I had a future in this and I’m excited.”

The acclimation process was a rapid one for Barry; within weeks of joining Grunlan’s lab, she was producing the polymer coatings for the catheters and studying how the coatings interacted with the devices on which they were applied.

“She took a typical path that a lot of our undergraduate student researchers do, although she started earlier than is typical – being a freshman is quite young to start research,” Grunlan said. “She is a very bright and motivated student and has demonstrated a strong research ability.”

Barry acknowledged her initial days in the lab were defined by a steep learning curve.

“Those first couple of weeks were quite exhausting, but considering where I am now, I am really glad I was put in head first because it gave me such a great opportunity to grow as a researcher and scholar,” Barry said. “While it’s a lot of time investment, it’s also time that is invested in my ability to learn, and what I learn in the lab corresponds with other things that I’m learning in my classes.”

It’s the ultimate hands-on experience for someone with Barry’s aspirations. Spending about 10 hours a week in the lab, she conducts a range of experiments and tests that involve not only manufacturing the polymer coating but constantly measuring its effectiveness through a variety of different techniques that enable her to assess and refine the design of the coating.

This coating, Barry explains, works by blending in a polymer additive that when incorporated into the main catheter material causes a specific interaction when the device surface contacts blood. When this happens, she says, a molecular reorganization of the surface takes place, and a hydrophilic, or water-attracting, polymer blooms to the surface. Because bacteria and proteins don’t adhere well to hydrophilic surfaces the polymer coating prevents potential clots and infections from forming, she says.

“One of the greatest things about working in Dr. Grunlan’s lab is that while I am an undergraduate they don’t treat me like one,” Barry said. “They include me in all of the theory, and they help me understand why I’m doing what I’m doing. It’s not like a part-time job where I am just fulfilling tasks; it’s a learning experience that integrates what I am learning in the classroom with what I would like to do in a laboratory environment someday after I graduate.”

For now, it’s a fast and furious start to an academic career that’s already seen Barry honored as Texas A&M’s first Beckman Scholar through an intensive written application and interview process that probed her goals, values and commitment to a career in scientific research and community service. The award honors the memory of Arnold O. Beckman. Beckman was founder-chairman emeritus of Beckman Instruments, Inc., and inventor of several scientific instruments, including the Beckman DU Spectrophotometer, which revolutionized chemical analysis.

Through the scholars program, Barry and Grunlan attended the Beckman Symposium in Newport Beach last summer to meet other Beckman Scholars and mentors and hear presentations from prominent scientists from across the nation.

Now a sophomore, Barry is engaging in additional activities as part of her Beckman Scholars Program. She is part of the first-year University Scholars seminar through which she is further developing her leadership skills. In addition, she meets periodically with the executive and editorial boards of “Explorations: the Texas A&M Undergraduate Journal” to discover how review and publication decisions are made, and she is preparing applications for several national fellowships in STEM areas.

“Those first couple of weeks were quite exhausting, but considering where I am now, I am really glad I was put in head first..."

Barry also has taken on leadership roles in the Texas A&M Wind Symphony and Advocates for Christ Today, a church-based social justice organization, while maintaining a 4.0 GPR and her status as an honors student in the Dwight Look College of Engineering Honors Program.

This spring, she will present her research from Grunlan’s lab at a meeting of the National American Chemical Society in Denver where she will have the opportunity to speak with people from around the world about her work and also learn more about graduate school and a career in the biomaterials field, areas Barry intends to pursue with the same fervor that’s characterized her undergraduate studies.

“After I graduate from Texas A&M with my biomedical engineering degree I hope to continue graduate studies, preferably in polymer chemistry or some sort of biomaterials field,” she said. “I would like to earn my Ph.D. and do postdoctoral research and become a faculty member at a research university where I can be in a position to enable other undergraduates with the same type of experience I am having with Dr. Grunlan at Texas A&M.”